Staff Post

By Heather Young

Accounting logic says that your financial statements must be denominated in one currency. Many organizations make regular payments to foreign artists, suppliers and others – so how can they record the transactions correctly?

Let’s take two cases.

In the first instance, let’s assume you only have a Canadian dollar bank account. That means you’re purchasing foreign currency (e.g. bank drafts or wire transfers) as needed. The bank calculates the cost in Canadian dollars by applying today’s exchange rate. This becomes your expense.

Suppose you’ve engaged an American soloist and agreed to pay them $2,500. The day you purchase the US draft, the US dollar is trading at 1.23. Your artist fee expense becomes 2,500 x 1.23 = $3,075.00, and you’ll see that amount being withdrawn from your Canadian bank account.

In this instance, the $2,500 US dollars don’t appear in your accounting records: the only value that counts is the Canadian equivalent. And, yes, that amount depends on the day! Yesterday the US dollar might have been worth 1.22 and tomorrow it might be 1.24! That doesn’t matter: what counts is the prevailing rate on the day of the transaction, because that determines how many Canadian dollars came out of your account. It is important to add a memo/note to the journal entry to indicate that the fee was $2,500 US dollars. This will create a link between the original fee agreement and the amount withdrawn from the bank, in case it is ever in question.

The process is different – and a little more complicated – if your organization owns a US dollar bank account. Now, the $2,500 US dollars must be part of your accounting entry, because that’s the number of US dollars you’re expending. Your accounting system must accomplish the following:

Record the number of units of the foreign currency you hold. (So, if you have $3,456 US dollars in the US bank account, that’s the number you should be looking at on your balance sheet.)

Record the correct value of that asset. (So, if you have $3,456 US dollars and today’s rate is 1.23, those US dollars are presently worth $3,456 x 1.23 = $4,250.88 Canadian.)

Record US revenues and expenses at the Canadian equivalent. (So, if you’re using $2,500 of those US dollars to pay your soloist, you must record an expense of $3,075 as calculated above.)

Many organizations deal with the problem by pairing the US bank account with a second asset account, named “Revalue US Dollars” or something similar. The foreign bank account captures the number of units of the foreign currency you hold. The paired account captures the difference in value to the Canadian dollar.

Thus, if your organization held $3,456 US dollars and the exchange rate was 1.23, the Revalue US Dollars account would contain $794.88.

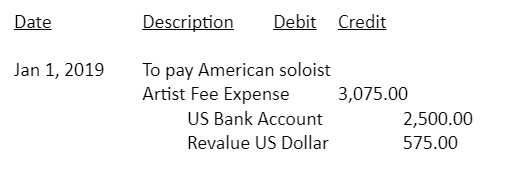

Your entry to pay the American soloist would look like this:

This entry states the true cost of the soloist; it updates your US bank balance correctly; and it revalues your asset (those US bucks) according to today’s exchange rate.

Let’s take another example – a deposit. Suppose an American visitor paid for their ticket in US dollars. If they paid $45.00 US a day when the US dollar was worth 1.23, your entry would look like this:

Now: the face value of that ticket may have been some other amount. But, as a matter of fact, at today’s exchange rate you made $55.35 Canadian – so that becomes your revenue.

As the month proceeds, you might have any number of transactions, each valued at the day’s exchange rate. Because the rate floats up and down, the amount in your “Revalue US Dollar” account eventually becomes inaccurate. For that reason, it’s important to “true up” the value of your US dollars from time to time.

Many organizations would make a separate entry on the last day of the month to update their US currency to the month-end rate.

Using the examples above, we started with $3,456.00 US dollars. We spent $2,500.00 and deposited $45.00 – bringing the account balance to $1,001.00.

And, the Revalue US Dollar account started at $794.88; we subtracted $575.00 and added 10.35, bringing the account balance to 230.23.

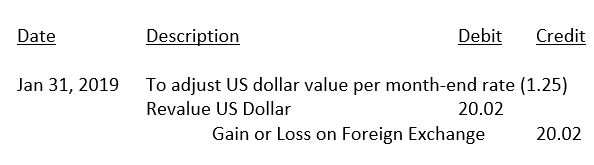

Let’s say that the exchange rate on the last day of the month was 1.25. At that rate, our $1,001.00 is actually worth $1,251.25. Our month-end balance sheet misstates the value of the US dollars. The following entry “trues up” to the current Canadian equivalent.

Note that this adjustment isn’t tied to any particular transaction: it simply corrects for the month-end exchange rate. The “pick-up” is allocated to a revenue account that specifically captures currency gain or loss. In months when the US dollar increases in value, you show a gain, because your “greenbacks” are worth more. But, when the Canadian dollar surges, you show a loss on your American currency.

These techniques allow you to have a foreign currency bank account – while still ensuring that your asset, and your revenues and expenses, are properly stated at their Canadian values.